In 1986, the Industrial Commission and the State Bank were embroiled (and embarrassed) in the infamous “Honduran potato deal.” The idea was to ship four million pounds of ND seed potatoes to Honduras, part of H.L. Thorndal’s quest to find foreign markets for North Dakota commodities. The Bank’s role was to issue $1.85 million in promissory notes to facilitate the deal.

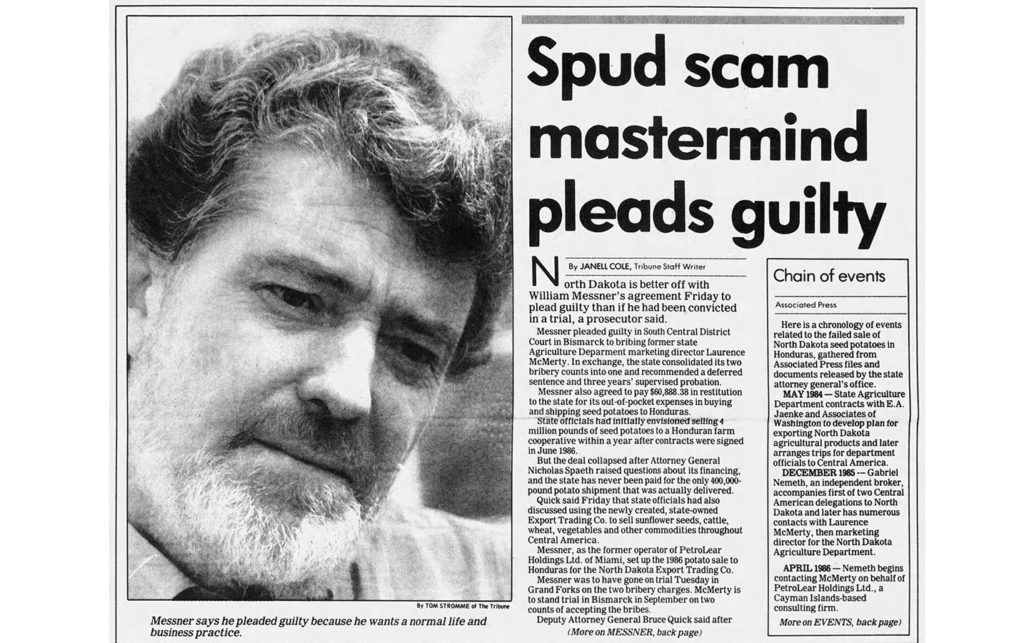

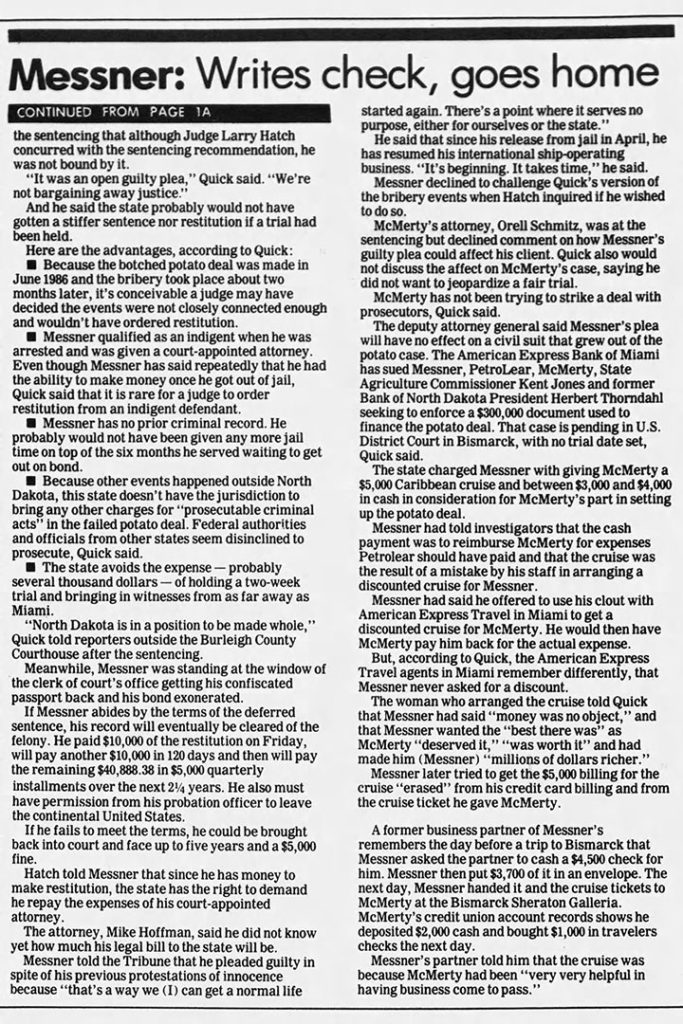

Unfortunately, the nation of Honduras had no money with which to buy the potatoes, and the promoter of the scheme, Canadian broker William Messner, proved to be a colorful but insolvent con man. Messner arranged for ND Agriculture Commissioner Kent Jones and others to visit Honduras, where they were feted and whisked about in motorcades to their meetings with the country’s top political leaders. The whole deal proved to be a house of cards, and North Dakota’s Attorney General Nick Spaeth, elected in 1988, ruled that North Dakota wasn’t liable for the note.

Eventually, Messner pleaded guilty to federal bribery charges. He died in 1988. Jones and Thorndal were cleared of legal wrongdoing, but a subordinate in the Agriculture Department pled guilty to accepting compensation for a government transaction.

The whole unsavory business made the State of North Dakota and its “socialist” Bank look like rubes–so desperate for new commodity markets that it would fall for what appears to be an obvious con job. This may be so, but the incident has to be understood as another indicator of North Dakota’s historic “colonial” status.

From its inception, the Bank was intended to help diversify North Dakota’s narrow agricultural economy. In the early years, the Nonpartisan League attempted to create successful investments in an Alaska fishery, a Florida sisal company, and a chain of cooperative general stores in North Dakota. All of these enterprises failed, at a significant cost to the credibility of the League and its state institutions.

The 1980s Honduras potato scam represented yet another attempt by North Dakota’s Industrial Commission and the Bank to improve the economy of a state that still depended, five decades after the adoption of the Nonpartisan League program, on uncertain markets and raw commodity sales. If the Honduras scheme had worked, the Bank and the Industrial Commission would have won accolades from the Legislature and the people of North Dakota.