During the 1950s, the national conservative backlash against Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal achieved virulent proportions. This was the era of Joseph McCarthy, the House Un-American Activities Committee, “communist infiltration,” and the real or perceived theft of America’s nuclear secrets. Anything savoring the aroma of socialism or social engineering was suspect during this period of American history. There was a national attempt to dissolve Indian reservations, undo Social Security, and roll back every remaining New Deal program.

Bizarrely, A.C. Townley, the populist firebrand who had created the Nonpartisan League in 1915 and presided over it during its headiest years, now rebooted himself as a snarling anti-Communist stump speaker. The managers of the Bank of North Dakota wisely kept their heads down, went about their business in the least-controversial manner, and avoided publicity during this period of reaction. Their goal was survival.

By 1959 the Bank had stopped making farm loans. Thus, one of the principal purposes for the Bank’s creation in 1919 had ceased–40 years later–to be one of the Bank’s roles in North Dakota. By then the Federal Farm Program had become the principal guarantor of farm loans in North Dakota. Essentially, the New Deal and its program descendants had taken the place of the Bank in providing economic stability for the nation’s farms. By now the Bank of North Dakota was primarily a depository for public-entity funds in North Dakota. Its modest home loans program was one of the few services available to individual North Dakotans.

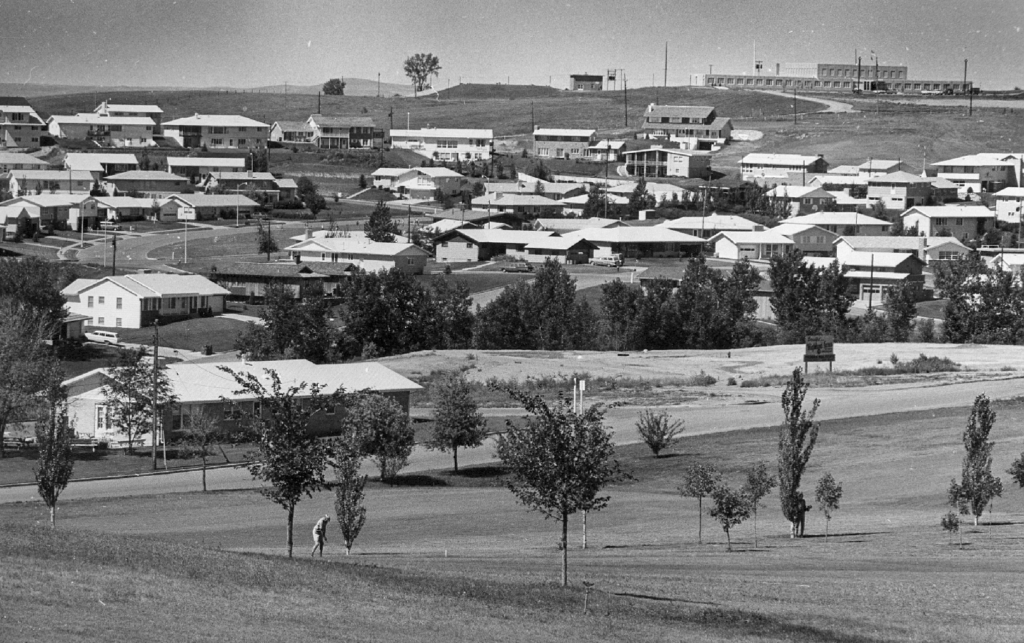

The years from 1945 to 1960 were “an exceptionally quiet time for the Bank,” according to Rozanne Enerson Junker, the author of a history of the Bank published in 1989. After the crisis of the Great Depression, exacerbated by the extra-constitutional efforts by Governor William L. Langer to hold the state together through its greatest crisis, the leaders and people of North Dakota “were content to run the Bank primarily as a depository of the state’s funds.”

Through the first hundred years of the Bank’s existence, a fascinating pattern developed. The Bank raised its profile and took significant risks to help North Dakota through difficult times, then slipped below the radar when conditions improved, both because its job was temporarily done and to avoid calling attention to itself. Periods of progressivism tended to alternate with periods of retrenchment and retraction. After periods of intense activity, the Bank tended to embrace the least “exposed” and controversial profile, quietly doing its core work and accumulating capital and credibility, until the next time it was needed to prop up the state.

The Bank’s second transfer of funds to the general fund was made in 1951. In 1953, the Bank supplied $9.6 million to match federal highway funds. This was the first occasion when funds from loan collections were transferred to the state’s general fund, rather than earnings (such as mineral revenues) unrelated to the Bank’s loan portfolio. Thanks to these precedents, during economically difficult times in North Dakota, the Bank was increasingly called upon to make transfers to meet budget shortfalls.