Forces From Many Sides Brought Down the League

The League failed for a number of reasons. It over-reached both geographically and in mission-creep. There was only one A.C. Townley; nobody has his ability to create enthusiasm.

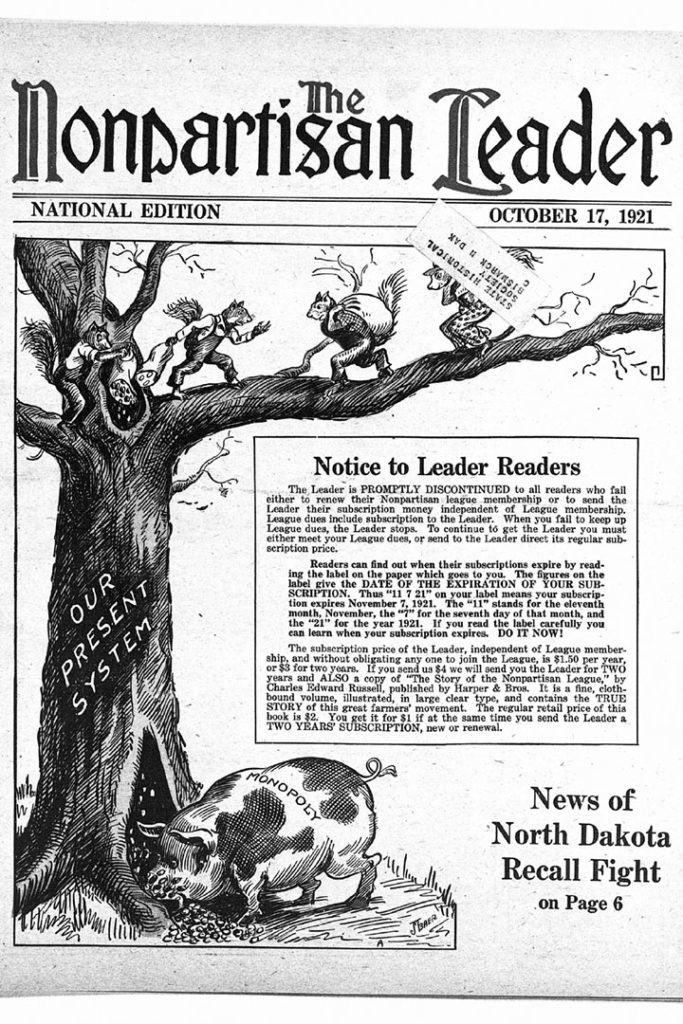

The forces of reaction in the business community, once they understood the insurrection, proved to be clever and ruthless. And, perhaps most significant of all, World War I changed the whole dynamic of life on the Great Plains. Even those who sympathized with the League’s program were distracted by calls for national unity during the War. The Red Scare that swept the nation was the most severe test of the Bill of Rights in American history.

Against the waves of nationalism, hyper-patriotism, and jingoism that rolled over the continent between 1917-1920, the NPL could not flourish. In 1918, the Bismarck Tribune wrote, “Vote as You Would Shoot! There is only one issue in North Dakota. That issue is LOYALTY.”

The Cataclysm of World War I

Once the United States entered World War I, NPL supporters were accused of stirring domestic waters at a time of international emergency; of impeding recruitment in the US Army; of treason; and of being un-American. The world war probably had more to do with the stalling of the League’s success than any other single factor.

The world war put the Nonpartisan League on the defensive in three distinct ways. First, it sucked the oxygen out of the League’s mission. As the United States mobilized for war, the concerns of “a bunch of disgruntled farmers” in North Dakota were made to seem selfish and parochial. The urgencies of world war were such, League critics argued, that domestic concerns, even legitimate ones, should be postponed until after the successful prosecution of the war. An agrarian uprising during a time of national and international emergency was regarded as disloyal.

Second, although the League’s response to the war was nuanced and never actually disloyal, it was easy enough for the League’s detractors to emphasize every statement by Townley, Lemke, and Joseph Gilbert that was not 100% patriotic and jingoistic, and to quote League leaders out of context to impugn their loyalty. William Lemke was offended by the anti-German pronouncements of men like former President Theodore Roosevelt but, once the United States entered the war, he committed himself unhesitatingly to America’s position. Still, as historian Edward Blackorby writes, “As did many others, he found it easier to feel and express loyalty to the United States than to convince others that he was loyal.” If this was true of Lemke, it was truer still of A.C. Townley. The Bank of North Dakota suffered by association.

Finally, the Nonpartisan League may have collapsed no matter what, but the coming of the war brought boom years to American agriculture. Born of economic desperation, the League ceased to be so attractive when prices rose to historic levels, permitting North Dakota’s farmers to set aside their anger at exploitation by outside interests.

Historian Edward C. Blackorby, who wrote biographies of William Lemke and Usher Burdick, believed that if World War I had not interrupted the movement, the Nonpartisan League would have become a serious national party. At one point, League leader William Lemke began to prepare the League’s farmer-candidate Lynn J. Frazier for the possibility that he might eventually run for the presidency of the United States.

The legacy of the Nonpartisan League.

- North Dakota has the nation’s only state-owned bank, the Bank of North Dakota, located on the east bank of the Missouri River in Bismarck.

- North Dakota has a state mill and elevator in Grand Forks.

- The three-member Industrial Commission was created in the 1919 legislative session to “manage, operate, control and govern all utilities, industries, enterprises and business projects, now or hereafter established, owned, undertaken administered or operated by the State of North Dakota.” The Industrial Commission still exists.

- No matter what politics the commercial or establishment entities of North Dakota pursue, there is always the sense that in the people of North Dakota there is a streak of populist distrust of entities that do not originate in and cannot be controlled by the people of North Dakota.