Farmers were paying up to 12% interest. Grain elevators graded grain as lower quality and farmers lost up to $55 million each year. Rail cars were poor quality, losing grain along the way. Farmers were paid based on the delivered weight. To transport 60,000 pounds of wheat from Minot to Grand Forks, a farmer was charged $91.80; Moorhead to Minneapolis which was 45 miles further was $61.80. These economic realities served as good fuel to the NPL fire.

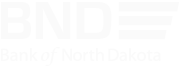

An organizing machine

Townley and his cohorts attempted to organize the farmers of North Dakota before opposition could be developed. Many of the newspapers of the state were caught off guard. Because they regarded themselves as the natural clearing houses for all developments in their districts, most of those newspapers responded with skepticism or open hostility. With little solid information in their hands, they groped in the dark to try to understand what was happening in the rural countryside. The Kidder County Ozone’s response is typical:

“Recently the Ozone referred to the presence in the state of a number of solicitors for membership in some kind of ‘party’ which was to be of special advantage to farmers, and who also offered a year’s subscription to some paper or magazine as material inducement for joining. A fee of $6 was collected from each subscriber … It is more than ever evident that the farmers who took stock in the smooth strangers were too easy victims of a confidence game. In no case have the strangers sought to interest anybody in towns where they have stopped, and it has been noticed that in making even a trifling purchase they always tender $6 checks, cashing them in that way. They never go to a bank … As before stated, the Ozone believes, with the Fargo newspapers, that this is only a scheme for fleecing the unwary … Our belief is that they are operating a questionable scheme, as there is no public knowledge of such a farmers’ protective party as they affect to represent, and their avoidance of association or contact with townspeople, and advance dating of checks are suspicious.”

One of the League’s most effective organizing tactics was the use of the post-dated checks. Townley rightly understood that farmers would only remain committed to the League and its program if they had “skin in the game.” But most farmers did not have enough ready money to pay for their League dues. Townley instituted the use of post-dated checks, to be cashed after harvest, so that each farmer would invest in the League at the time of his recruitment, before the spell of the salesman’s charisma wore off. Although many commercial banks refused to honor these checks, and though some farmers canceled payment after the initial intoxication of Townley had dissipated, the League’s use of this organizing tactic made a huge, arguably, essential contribution to the early success of the Nonpartisan League (NPL).

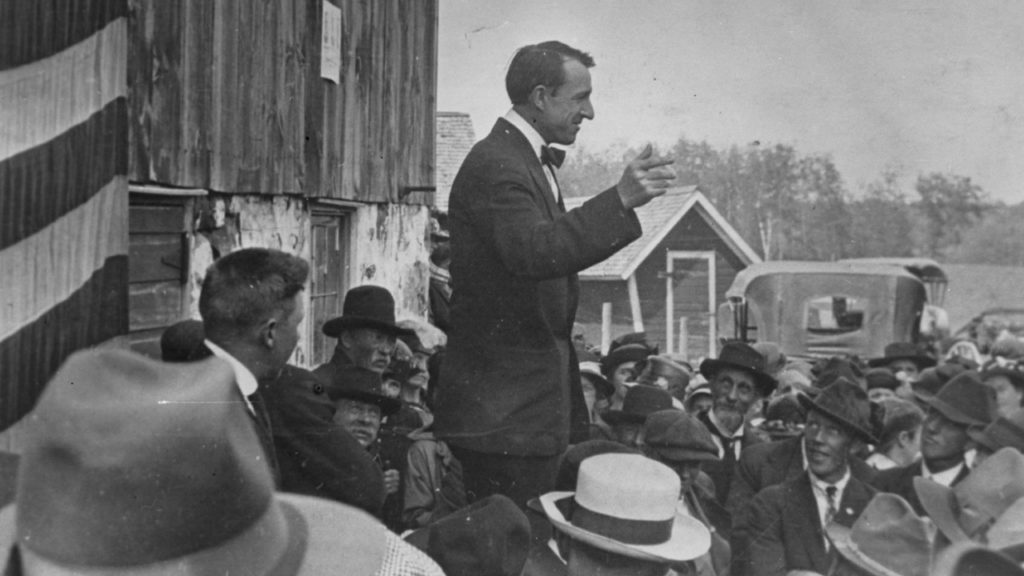

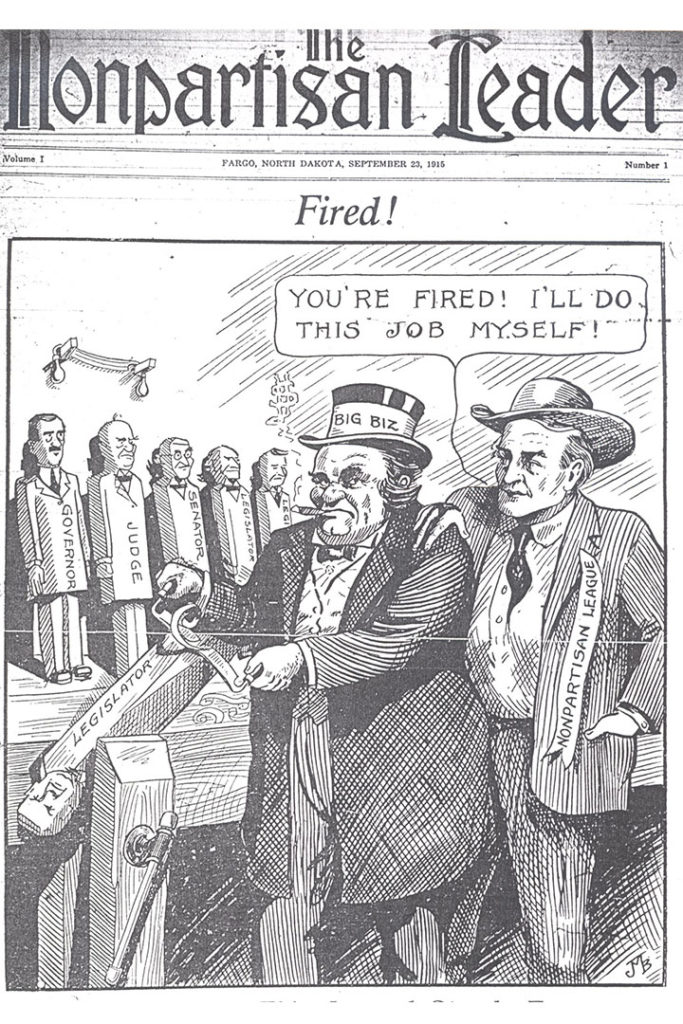

The Nonpartisan Leader

Townley understood that once the League began to seem like a viable political movement, opposition would be fierce, well-funded and ruthless. He knew that most newspapers in North Dakota would side with the established order. Almost immediately, therefore (September 1915), Townley and the League launched the Nonpartisan Leader, a lively, provocative, well-edited weekly League newspaper, headquartered in Fargo. Soon the League purchased its first daily, the Fargo Courier-News. The League also organized something called the Northwest Publisher’s Service to purchase local weekly papers and to coordinate the League’s plan to designate official newspapers (friendly to the League) in every county of North Dakota. The Northwest Publisher’s Service was one of the most controversial innovations of the NPL.

The NPL in Minnesota

In neighboring Minnesota, Charles A. Lindbergh (the father of the famous aviator) ran for governor on the NPL ticket in 1918. During one rally, his driver was roughed up by an anti-League mob until Lindbergh personally intervened. As the League cohort left the grounds, bullets were fired at their automobile. Lindbergh insisted that they drive away slowly to make it appear that they were not frightened by the violence. They were frightened, of course, but Lindbergh insisted that rushing away would only encourage further mob violence.

Public Perceptions

The League’s stunning success in the 1916 elections in North Dakota brought journalists from all over the United States to the legislative session of 1917. Many made fun of the “rubes” and “yokels” who now controlled the North Dakota House of Representatives and dismissed them as “tools” of “Boss Townley” and his henchman William Lemke. William MacDonald of The Nation, however, was surprised and impressed:

The farmer legislators, he wrote, were “…neither visionary theorists nor wild-eyed radicals… I have seldom observed a State legislature whose controlling majority was so obviously sensible, moderate and intelligent. The extremist of every type, the voluble expounder of radical notions, or the reformer with his one all-sufficnet remedy for social ills, was conspicuously absent.”

Name Calling

Supporters of the Nonpartisan League were called many things: “red Socialists,” “expert hypnotists,” “gold brick vendors,” “world revolutionaries,” “atheists,” “IWWs,” “dynamiters,” “free lovers,” “carpetbaggers,” “home wreckers,” “Huns,” “traitors,” “noisemakers,” “theorists,” “dilettantes,” “dreamers,” “beautiful phrasemakers,” “swivel-chair reformers,” “mild-eyed poets,” “sweet-mouthed flatterers,” “mountebanks,” “confidence men,” “anarchists,” ”charlatans,” “agitators,” “visionaries,” …

Minnesota judge John F. McGee said, “a Nonpartisan League lecturer is a traitor every time. In other words, no matter what he says or does, a League worker is a traitor.” Judge McGee said what Minnesota needed was a few “necktie parties.”

Some of these epithets were ludicrous and profoundly unfair. A few had a kernel of truth. But they all indicated that the opposition was more interested in name calling than in a serious debate about how to address the fundamental economic and political issues of North Dakota. The “dynamiters” and “noisemakers” were actually just family farmers trying to get a better price for the food they grew to feed the people of America.

The League platform

The League program was virtually identical with the program of the North Dakota Socialist Party: a system of state enterprises, including a terminal elevator and flour mill, rural credit banks, state hail insurance, state-owned packing houses and cold storage plants; plus, reform in grain weighing and grading practices, and the exemption of farm improvements from taxation.

What the League offered was a moderate program of socialism without the Socialists. Most of the farmers of North Dakota were sensible pragmatists, not ideologues. North Dakotans did not want to be labeled as radicals, subversives, or members of the Socialist Party, but-–it turns out—they were not afraid to embrace a handful of “socialist” solutions to their chronic economic problems.