Nobody is quite sure where the idea of a state-owned Bank of North Dakota came from. League officials, including Governor Lynn J. Frazier, had spoken frequently of “a system of rural credit banks operating at cost,” (a kind of rural credit union system), but the idea of a central state bank did not enter the discourse until 1918 and 1919. A booklet published by the League on August 31, 1918, called for a “State Bank which will act in a similar capacity for our state as does the Federal Reserve and Farm Land Banks. . ..”

Conservative representative Paul Johnson of Mountain, North Dakota, wrote, “The bill looks to me to be socialist in the main points. I do not believe in state-owned and operated utilities: at least I do not believe in experimentation on a large scale like this.”

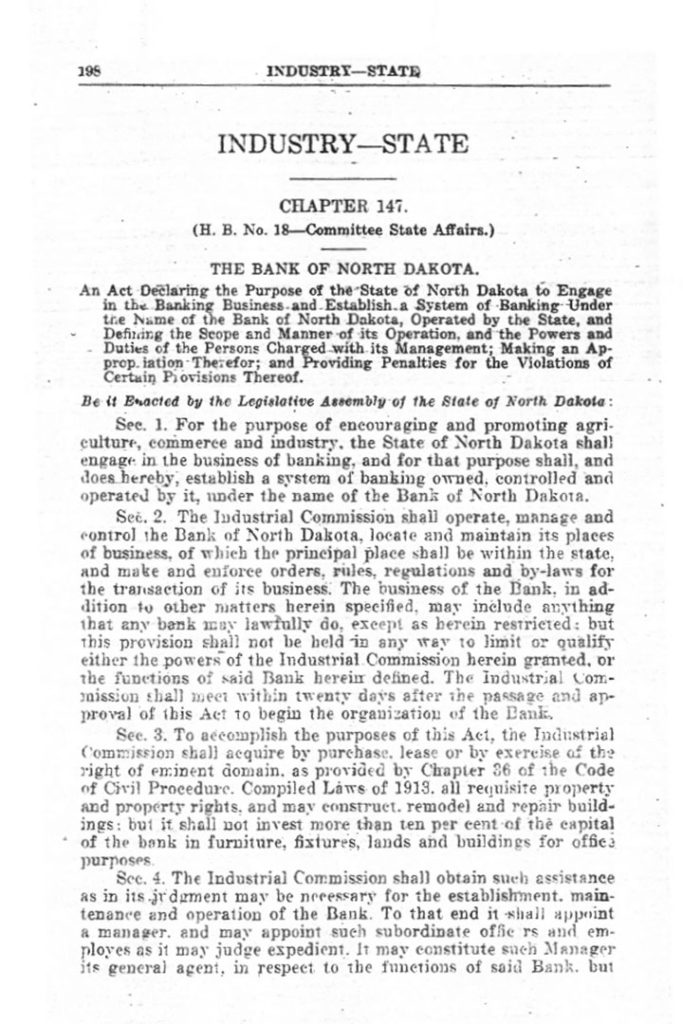

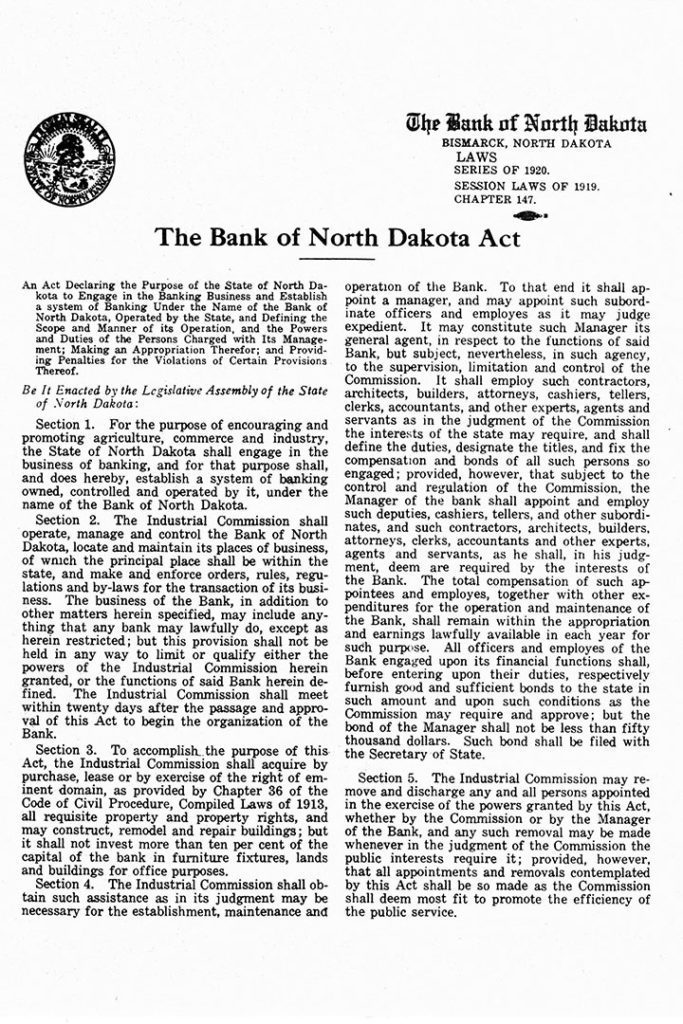

The 1919 North Dakota legislative session, taking its cues from the Nonpartisan League’s Industrial Program for North Dakota, created the Bank of North Dakota. The legislation declared that the Bank was “created for the primary purposes of providing low-cost rural credits, financing state departments and enterprises, and serving as a clearinghouse and rediscount agency for banks throughout the state.”

The NPL prepared a memorandum of recommendations during the 1919 session and presented it to the House and Senate of North Dakota. Article 7 said: “That the state should establish and operate its own bank, for the financing of all state departments, industries and enterprises, for the handling of all public funds and for the making of farm loans and the stabilizing of credit in all industries carried on in the state.” This was the founding document of what became the Bank of North Dakota.

In the end, the League program was reduced to one large state mill and elevator (in Grand Forks), and one state bank (Bismarck). This centralization of what was originally a vision of a myriad of decentralized banks, elevators, and mills undoubtedly reduced the effectiveness of the monumental entities, but-–ironically—they probably insured their survival. It seems certain that the decentralized array of smaller institutions would have been swallowed up by the dynamics of North Dakota history. The two central institutions—the State Bank and the ND Mill and Elevator—were, in a sense, too big to fail, or at least too big to for League enemies to kill off with impunity.

After the landmark ND legislative session of 1919, even the hostile Grand Forks Herald wrote:

“The session was the most important in the history of the state, and it accomplished the most far reaching legislation yet enacted. The state is now the socialistic laboratory of the country, and unless the people veto the administration measures the experiment soon will begin… The most interesting experiment in the history of the country will be carried out in this state during the next two years.” The Herald concluded, “There is nothing Bolshevist, so far….”

The original guiding principles of the Bank of North Dakota

The Bank could transfer funds to other departments, institutions, or enterprises of the State of North Dakota.

The Bank could make loans to political subdivisions or to state or national banks.

Loans to individuals, associations, or corporations must be secured by mortgages on real estate or warehouse receipts.

The Bank of North Dakota was to be examined by state examiner twice per year followed by a report to the Industrial Commission and the North Dakota Legislature.

An initial $100,000 was appropriated to establish the Bank.

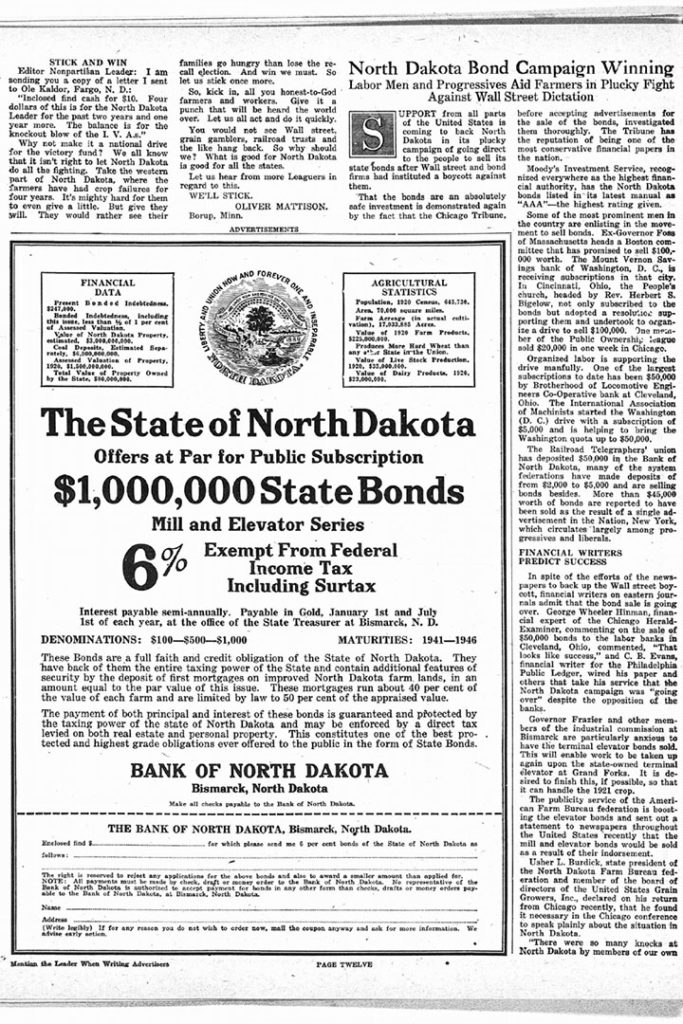

The Bank could commence operations as soon as it received $2 million from sale of state bonds authorized for capital.