The farmer citizens of North Dakota wanted to address certain serious problems of North Dakota economic and political life—exploitation of the people by out-of-state entities, such as banks, railroads, elevators and milling companies. They had long believed that a terminal elevator, probably located elsewhere but perhaps in North Dakota, would give them more control of the principal commodity of the state, small grains.

The NPL was the political instrument that addressed these problems. The NPL was not necessarily the ideal instrument, because it was born out of the Socialist Party, which most North Dakotans did not support; and because A.C. Townley was a problematic genius, who brought about the revolution but became a lightning rod because of radical rhetoric and his insistence on complete control of the League. The NPL brought about the state mill and elevator in Grand Forks, state hail insurance, the Industrial Commission, and the State Bank of North Dakota, among other reforms, but only the state mill was widely popular. It had been a key part of the farmer agenda for years before the birth of the Nonpartisan League.

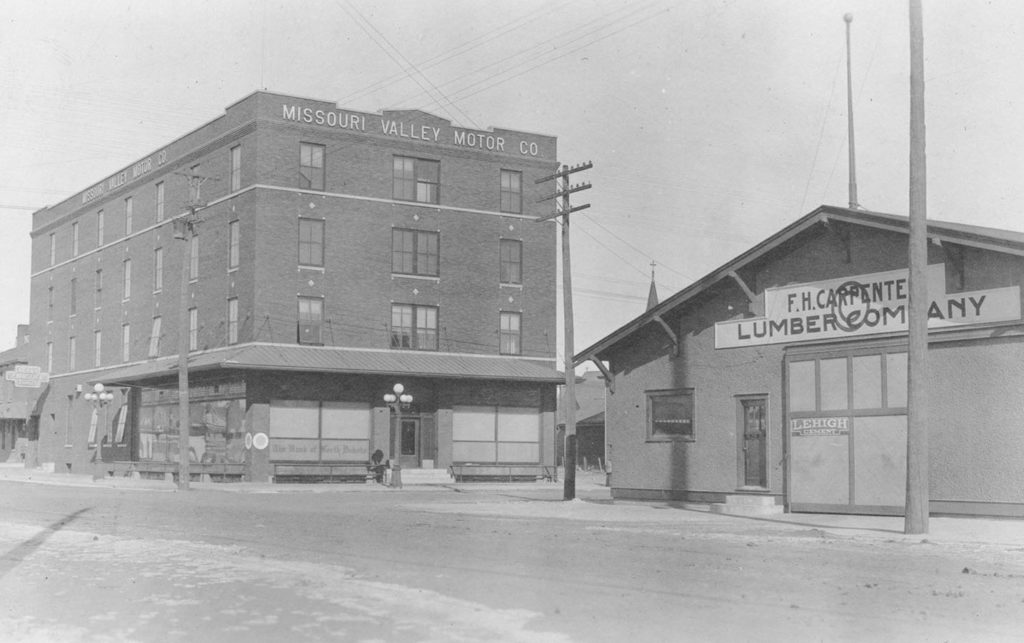

The state-owned Bank in particular was seen by many North Dakotans as a dangerous and unnecessary innovation. The farmer citizens of North Dakota did not really seek a socialist economy; they merely wanted redress of grievances. If reforms could be accomplished without a wholesale economic and political revolution, most North Dakotans would have been more satisfied than they were with what many regarded as the radical agenda of the League.

League mismanagement of some of the new industries, League punishment of its enemies, and certain hints of authoritarianism (the anti-liar’s law, the Committee of Investigation, the state sheriff law, for example) convinced citizens who endorsed much of the League’s program that the NPL was flirting with authoritarianism. Still, even when the conservative reaction recalled Governor Frazier and discredited Townley and others in the League leadership, the people of North Dakota chose to keep the state mill and elevator and the State Bank of North Dakota alive, to give these innovative experiments a genuine chance to improve conditions in the state. Most North Dakotans were willing to give the League the benefit of the doubt on its response to America’s entry into World War I, but at the same time many North Dakotans were uneasy with the League’s lukewarm support for the war once it was declared in April 1917.

North Dakotans established the State Bank of North Dakota to provide a non-commercial alternative to the existing credit system on the northern Great Plains, particularly with respect to agricultural loans. The Bank would provide credit to farms (and later ranches) below the commercial rate of interest, and with a somewhat more flexible protocol of collateral security. Social and economic experiments that would usually fail to find support in the commercial lending arena would be supported by a bank whose mission was to improve the lives of the people of North Dakota with a dedication to service and solvency rather than the maximization of profit. The very existence of the Bank of North Dakota would put traditional commercial lenders and other capitalist entities on notice that the people of North Dakota were prepared to take matters into their own hands and engage in bold social experimentation to improve their lives.