The easiest way to defeat the Nonpartisan League was to associate it with socialism and communism, or to accuse it of unpatriotic behavior or to deride the farmer citizens of North Dakota as rubes. The Dayton Press in Washington state wrote, “No wonder that the Nonpartisan bunk became so popular in North Dakota. The census taker found only five bathtubs in four counties. Uncleanliness and ignorance are ever companions, instance the Bolsheviki in Russia and the Bolsheviki hoboes of the I.W.W. and other unclean classes in the United States.”

Opposition to the League was fierce. NPLers were accused of being socialists, communists, anarchists and losers who preferred to seek government handouts rather than do the hard work of succeeding at farming. League supporters, especially political candidates, were subject to intense commercial discrimination in their hometowns.

The U.S. Supreme Court Challenge

On April 19, 1920, the nine justices of the United States Supreme Court heard appeals from Scott v. Frazier and Green v. Frazier challenging the constitutionality of North Dakota’s state-owned enterprises, including the Bank of North Dakota. The justices had a hard time understanding why the enterprises should be regarded as an infringement of the Fourteenth Amendment rights of North Dakotans.

Court (Justice James Clark McReynolds): “Why shouldn’t the state operate a bank?”

N.C. Young (representing the taxpayers): “It might properly do so for bona fide banking purposes of its treasury, but this bank is started merely to finance these industries.”

Court: “Well, and why should not the state go into business?”

Young: “Why, that is taking money from the taxpayer without due process.”

Court: “That is merely words. We are interested in reasons.”

On June 1, 1920, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the League enterprises in both cases.

Associate Justice William R. Day delivered the opinion of the Court. He declared: “If the State sees fit to enter upon such enterprises as are here involved, with the sanction of its constitution, its legislature, and its people, we are not prepared to say that it is within the authority of this Court, in enforcing the observance of the Fourteenth Amendment, to set aside such actions by judicial decision.”

Day said, “With the wisdom of such legislation, and the soundness of the economic policy involved we are not concerned. Whether it will result in ultimate good or harm it is not within our province to inquire.”

What mattered was that the Bank of North Dakota and the North Dakota Mill and Elevator were legal institutions.

As the Cincinnati Post put it, “the decision merely permits the people of a State to do what the majority wants done, and which is not in conflict with the Federal Constitution.”

The Independent Voters Association maneuvers

In North Dakota, the opposition formed the Independent Voters Association (IVA), but in neighboring Minnesota the opposition took on a more formidable name: Commission of Public Safety.

The IVA did not oppose the entire League program as enacted in 1919, but it did oppose two League programs with all its rhetorical force:

First, the Bank of North Dakota.

Second, the new Industrial Commission.

North Dakota historian D. Jerome Tweton wrote, “Nothing upset IVAers more than the thought of the state going into the banking business. The Independent [the IVA newspaper] dwelled on the failures of state banking businesses in American history and on the un-American and undemocratic philosophy upon which the Bank of North Dakota was founded. Especially distasteful to the paper and to the IVA was the requirement that all public funds be deposited with the bank and that control rest in the hands of the Nonpartisan League-controlled Industrial Commission.”

If the bank must exist, the IVA insisted that it be controlled not by politicians (the elected Industrial Commission), but by nonpolitical administrators.

The IVA tried to destroy the new state industries by way of hostile audits, and by cooperating with eastern financial interests to boycott the Bank or to purchase North Dakota bonds only if the state severely chastened its industrial enterprises. They worked hard in 1921 to reduce the Bank of North Dakota to a farm loan agency.

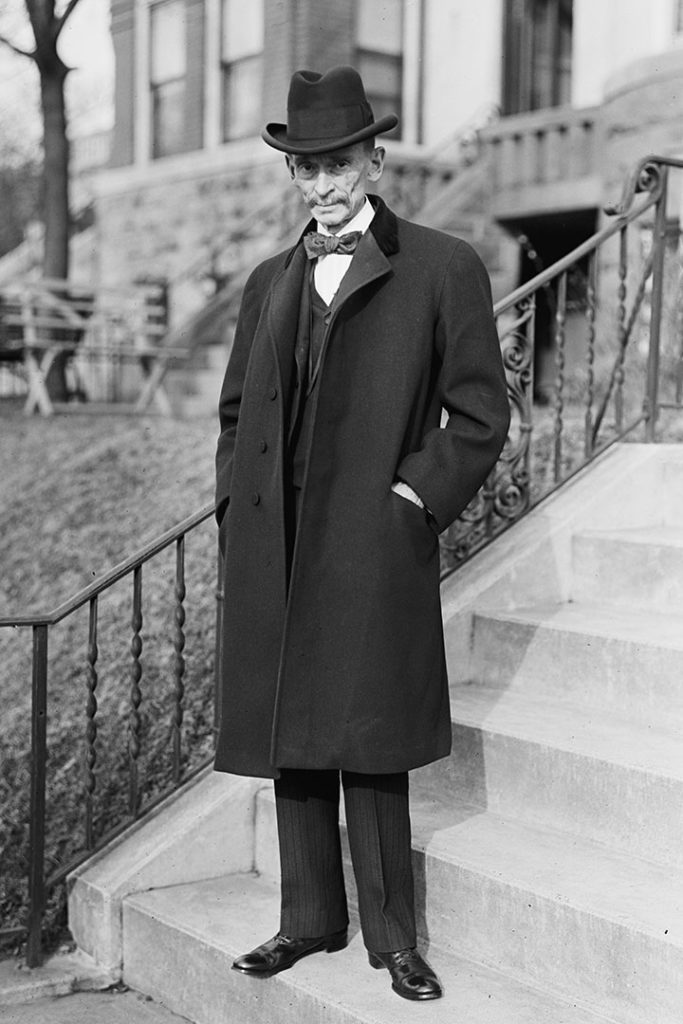

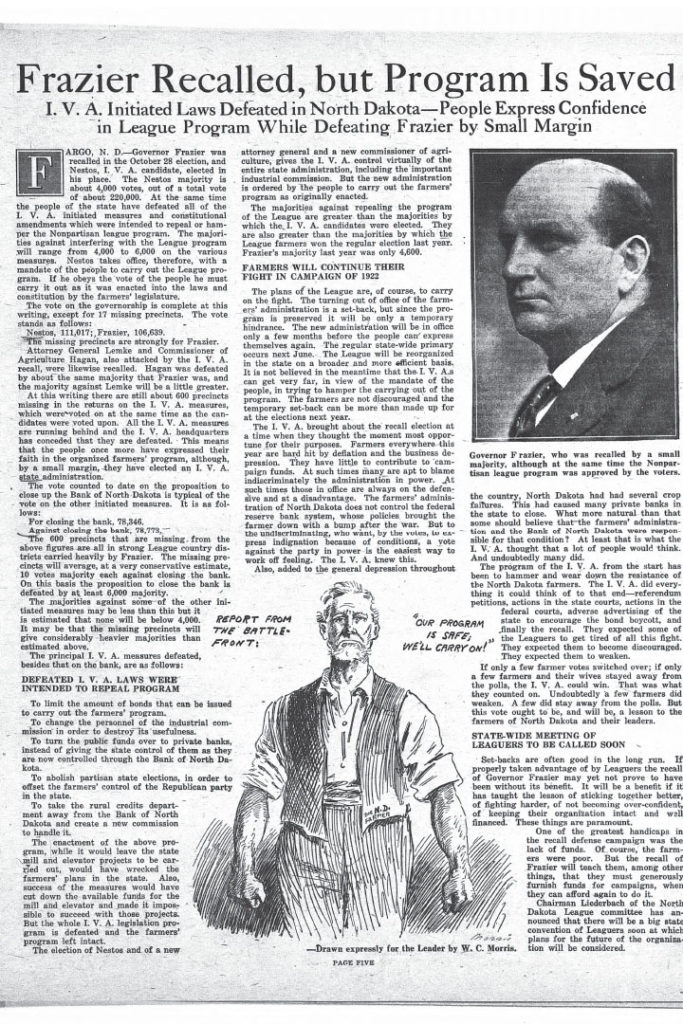

The showdown came on October 28, 1921, when League opponents recalled the three members of the Industrial Commission, including Governor Lynn J. Frazier, Agricultural Commissioner John Hagan and Attorney General William Lemke.

It was a dark day for the Nonpartisan League. The citizens of North Dakota had become convinced that the League leadership was incompetent and—according to some—corrupt. The recall was successful—all three League members of the Industrial Commission were recalled and replaced—but the opposition’s attempt to dismantle the League’s economic and Industrial Program through a series of initiated measures failed. By a margin of 4,238 votes, the people of North Dakota rejected a measure that would have abolished the state-owned Bank.

The most shocking decision was the recall of Lynn J. Frazier, the mild-mannered and thoroughly decent farmer-governor from Hoople, ND. Frazier was the first sitting governor to be recalled in the history of the United States. The next successful gubernatorial recall did not occur until 2003 when Gray Davis was replaced in California by Arnold Schwarzenegger.

The irony of Frazier’s recall is palpable. It was the Nonpartisan League that enacted recall, in the famous 1919 legislative session, to permit the people of North Dakota to engage, when necessary, in direct democracy. The people used their newfound power just two years later—to put an end to League management of the state industries created in 1919.

When the dust cleared, the people of North Dakota had determined to continue the economic experiment, but to put it into the hands of a different, more conservative, group of men.

The man who replaced Frazier as governor, R.A. Nestos, decided to manage the Bank in “a sane and conservative way” rather than attempt to destroy it. He agreed to give BND a chance to succeed. “It seems to me that it is but right and just and wise to give it a full, fair, and honest trial,” Nestos wrote.

All these maneuvers hurt the Bank both in credibility and in its attractiveness to outside investors, but none of the gambits was able to destroy the Bank or fundamentally emasculate its charter. The people of North Dakota wanted a state bank. They wanted it to be cautious, well-managed, humble and minimally profitable.

The Bank of North Dakota was fortunate to survive its birth pangs and initial growing pains. The provision requiring all local subdivisions (school boards, municipalities, county governments) to deposit their funds in the Bank of North Dakota brought on furious reaction and might, in itself, have caused the people of North Dakota to shut the Bank. The difficulty of selling the necessary bonds was worsened by the collapse of the private Scandinavian American Bank of Fargo, and by the lawsuits brought against the League’s Industrial Program—suits finally settled in the League’s favor by the US Supreme Court in June 1920. The bond boycott promoted by League enemies exacerbated the crisis. A certain amount of favoritism, cronyism and mismanagement in the early days of the Bank’s existence contributed to the view that commercial financial institutions—not state government—should manage the money supply of North Dakota. After an initiated measure freed local subdivisions of the necessity of depositing their funds with the Bank of North Dakota, the cash flow problem worsened.