The Case for a State-owned Bank

The credit system of the United States and the northern plains was not structured to meet the needs of North Dakota farmers in 1915. National banks could not lend money on farm mortgages. State banks could make farm loans, but they were under-capitalized, often dependent on money from out of state. Farmers were heavily dependent on store credit—buy food and hardware on credit now, pay for it after harvest—and insurance companies.

The Birth of the Nonpartisan League

The Nonpartisan League was born on a farm near Deering, North Dakota. In February 1915, A.C. Townley appeared at the farm of Fred B. Wood to pitch the idea of a new political movement that would not be tied to the Democratic, Republican or Socialist parties. Wood and Townley had met earlier in Bismarck. At that time Wood invited Townley to come to his farm in the spring after the snow melted.

NPL Gains Support

Farmers were paying up to 12% interest. Grain elevators graded grain as lower quality and farmers lost up to $55 million each year. Rail cars were poor quality, losing grain along the way. Farmers were paid based on the delivered weight. To transport 60,000 pounds of wheat from Minot to Grand Forks, a farmer was charged $91.80; Moorhead to Minneapolis which was 45 miles further was $61.80. These economic realities served as good fuel to the NPL fire.

A.C. Townley

A Failed Flax Farmer

A.C. Townley was a gifted rabble rouser, a talented political strategist, and, in the opinion of many, a demagogue. He was also a genius. After plunging into a bonanza flax farm north of Beach, North Dakota, and losing everything, Townley became a field organizer for the small North Dakota Socialist Party.

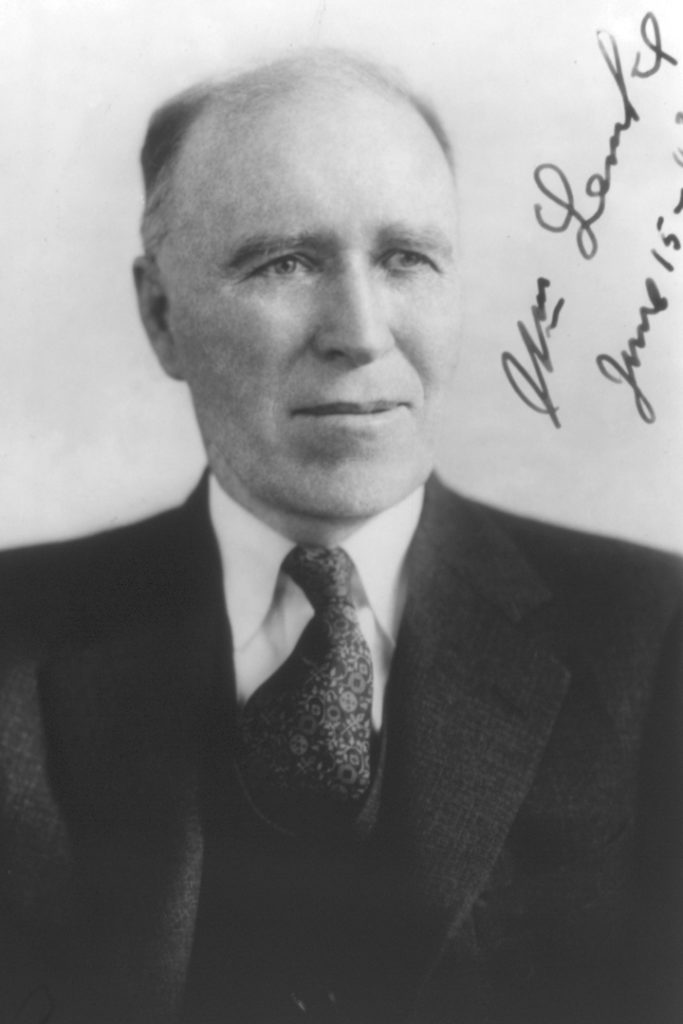

Lynn Frazier

North Dakota’s Cincinnatus

Lynn J. Frazier (1874-1947) was a farmer at Hoople, North Dakota, in Pembina County. Educated at the University of North Dakota, Frazier had never intended to take over the family farm, but the early deaths of his father and brother forced his hand. He had planned to be a doctor. He had taken on a few civic responsibilities in Hoople, including the school board.

William Lemke

The Political Bishop

William F. Lemke (1878-1950) was considered by many to be the brains of the Nonpartisan League. He was called “the political bishop” by some. He had known Bill Langer before the League was founded. He was practicing law in Fargo when he was recruited for leadership in the NPL in the summer of 1915.

The Birth of the Bank

Nobody is quite sure where the idea of a State Bank of North Dakota came from. League officials, including Governor Lynn J. Frazier, had spoken frequently of “a system of rural credit banks operating at cost,” (a kind of rural credit union system), but the idea of a central state bank did not enter the discourse until 1918 and 1919. A booklet published by the League on August 31, 1918, called for a “State Bank which will act in a similar capacity for our state as does the Federal Reserve and Farm Land Banks. . ..”

Open for Business

The enabling legislation in 1919 required that the new Bank of North Dakota must be open and doing business within 90 days of the adjournment of the state Legislature. The new three-member Industrial Commission went immediately to work.

Opposition to the Bank

The idea that simple farmers could chart their own destiny and win honest election to the highest offices in North Dakota appalled establishment institutions not only in North Dakota but across the United States. It was unthinkable that farmers had the intelligence, the political instincts and talent, and the organizational skills to change the trajectory of life on the northern Great Plains.

Taking Matters Into Their Own Hands

The farmer citizens of North Dakota wanted to address certain serious problems of North Dakota economic and political life—exploitation of the people by out-of-state entities, such as banks, railroads, elevators and milling companies. They had long believed that a terminal elevator, probably located elsewhere but perhaps in North Dakota, would give them more control of the principal commodity of the state, small grains.